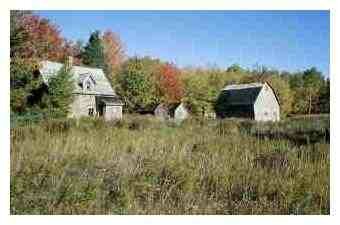

Jim inherited the property. A tired old rarm in Tennessee. He'd never seen it, and he had no semtimental attachment to it. And he needed some cash. He sold the land to Joe, the guy whose shop was next door to his for $100,000.

One month later, he goes to Joe, says he really misses being a landowner, and buys the property back for $110,000. A month after that, he sells the land to Joe again, for $120,000. A month later, he buys the land for $130,000, and a month later sells it again for $140,000.

On and on again, once a month, the property changes hands, and always at a price $10,000 higher than the previous month. The price was somewhere in the $350,000 range when one day Jim rushes into Joe's shop and says, "You'll never believe what happened. Someone down in Tennessee noticed that the land keeps getting sold, and the price keeps going up. He figured there must be oil under the land or something, and he just paid me a million dollars for the property.

Joe Was Unhappy

Joe was incredulous. "You sold that land for a million dollars?" Jim nodded, all excited. "How could you be so foolish? We've been going on for years, and we've each been making $10,000 every other month from selling that property! What are we going to do for an income from now on?"

I heard that story about half a century ago, and I know it's absurd and it's funny - but there's a little bit inside me that doesn't quite understand. Where did the money come from that they were making? And at this time in our nation's (and our world's) economic history, it'd be useful to know that answer.

I should admit that I spent the last week listening to the podcast every day of "This American Life' show called "The Invention of Money". Money is fiction, of course, and I understood that even before. Ira Glass and the folks at Planet Money do a bang-up job of explaining things, which is why I've spent an hour a day listening to this show.

But there's still a problem. In my gut, I know those guys are making money by selling the property back and forth, but they really aren't. It's like the farmer who loses more and more month every year by raising crops until he reaches retirement age, at which time he sells the farm, uses the money to pay off his debts, and moves to Florida with a gazillion dollars. I've known more than one farmer who followed exactly that formula to success by losing money.

Paging The Goat

And all of that leads to the Bob Barker goat puzzle. Every time it comes up, people argue about the results. Some argue that the counterintuitive answer is right, and you can prove it by running a simulation over and over. I disagree.

OK, here's the puzzle. You're on "The Price Is Right". You've won whatever is behind one curtain of your choice, and behind one of those curtains is a million bucks. You select one curtain. Bob Barker opens another. It's a goat. He then asks you if you want to switch curtains.

The supposed answer is that yes, you should. There's one chance in three that the prize is behind your curtain. There's a 67% chance it's behind one of the other curtains - and you know it's not behind the open curtain, because that's a goat, so you double your odds by opening another curtain.

The problem with that assertion is that it presumes that Bob knew that curtain had a goat. Anyone who ever watched the show knows that sometimes, Bob would open the curtain right away that had the big prize.

In Actual Fact

In actual fact, if Bob doesn't know what's behind the curtains, a third of the time, the prize will be behind your curtain, a third of the time, the prize will be behind the curtain that remains closed, and a third of the time, Bob will have opened the curtain with the prize and you wouldn't have reached this point.

And when you run the simulation that way, you find that it's a 50/50 proposition. It doesn't hurt to switch curtains. But suppose we make it a little different proposition. Bob tells you that you can switch curtains, but it will cost you $25,000 to do so. Should you switch? Definitely not.

We have here the makings of a good bar bet. Run your own simulation, perhaps with a pea under dixie cups. Tell the other guy that you're playing for the right to make a play for that drunken blonde in the corner booth. He chooses one cup. You flip over another cup. If it reveals a bean, you win the blonde and that's the end of it. If it doesn't, offer him the opportunity to switch cups for a double-sawbuck.

Winning The Proposition Bet

Your sucker knows from having been exposed to this game before, that his odds are 67% of winning if he changes, so he forks over the $20. In fact, the odds are 50/50 at this point, so you have a 50/50 shot at winning both the drunken blonde and the $20.

Better yet, if you win the blonde, tell him that for another $20, he can have the blonde anyway. The drunk ones aren't good for much, anyway. It's the sober and enthusiastic blondes that are the most fun.

Other Bloggers On Related Topics:

Bob Barker - curtains - farmers - fiction - goat - inflation - Ira Glass - money - This American Life